One of the unfortunate aspects of this world is that sometimes good intentions lead to terrible results. There is even a cliche, but true, aphorism about this; “the road to hell is paved with good intentions.” Just look at the results of prohibition (and the modern drug war) or abstinence-only sex education and it’s clear how good intentions can lead to terrible results.

We’ve encountered enough situations on our trip to start to see this as a recurring trend, and since some of these are really counter intuitive I thought it would be worth writing a blog post about it.

Giving money to beggars

Picture a young Filipino child, clothes tattered and face brown with dirt, pulling at your clothes and asking for money. The average income where he lives is so low that even a few dollars – a negligible sum to someone who can afford to fly across the earth, would help feed his family for days. Giving him a few dollars would be an incredible kindness, right? The truth is the exact opposite.

In many places, the beggars (including children) are actually recruited by organized crime. Begging can be relatively profitable in places with large numbers of foreign tourists and the local gangs know this. Children are often forced to beg by these groups and punished if they don’t make enough. Furthermore, children are even purposely maimed to make them more look more needy and therefore get more money. If you don’t believe me, here are articles about the problem in China, in India, in Bangladesh, and in Senegal.

But what about the children who aren’t begging for organized crime? No, even if you could somehow tell the two apart, you still shouldn’t give. Giving encourages local families to send their children out to beg rather than attend school. It also gets them dependent on charity for income.

What about giving food instead of money? This seems like a better alternative, but there are still reasons to be wary. The first is that it still encourages dependence on charity rather than self reliance and the second is that you might actually be getting scammed (and your money going to organized crime). In Phnom Pen young women will come up to you and ask you to buy milk powder for their newborn. Many people who would not normally give money to beggars are happy to do this, because it’s a newborn, right? Unfortunately no, as soon as you buy the (overpriced) formula and leave the women sell it back to the shop owner for half the cost, splitting the money you gave them. This expat even speculates that the babies used for this scam are rented to the scammers and perhaps drugged. This just serves to reinforce one crucial point – as a tourist who doesn’t know the city and the people, you cannot know who truly needs your money.

What can I do instead?

It is much better to support the local businesses and entrepreneurs who are giving jobs to people in their communities. These also help feed people and lift them out of poverty, and provide them a sense of self-worth they can’t get from begging. One cool organization supporting street youth is called Friends International. They operate quite good restaurants throughout Southeast Asia and use them to train former street youth in the hospitality industry. Once they develop their skills at the restaurants they can move on to working at other restaurants or hospitality businesses in their cities. The food and service we received at the two of their restaurants we ate at was great! Romdeng in Phnom Penh is where we ate tarantula, and Khaiphaen in Luang Prabang is where we tried a traditional Lao dish with wood chips in it (expect this in the next strange foods post)!

In addition to supporting these businesses by using their services, you can also help make financing available to them. We personally find that organizations like Kiva do a great job of fulfilling this mission. Kiva helps connect those who want to help with entrepreneurs across the developing world who need loans to expand their small businesses. The additional cool thing about Kiva is that it has a social aspect where some healthy competition among friends and teams encourages everyone to lend more. If you’re interested, Kiva has a good write-up about micro-finance.

In addition, charity is great, but money should be given to a recognized international or local charity. Sites like Charity Navigator help keep charities accountable and prevent your from giving your money to crappy charities like the four massive cancer charities recently revealed as fraudulent. Good charities know who in their communities really needs help and who doesn’t, and they are able to help those who need it most. Most often those are not the people you see begging on the streets.

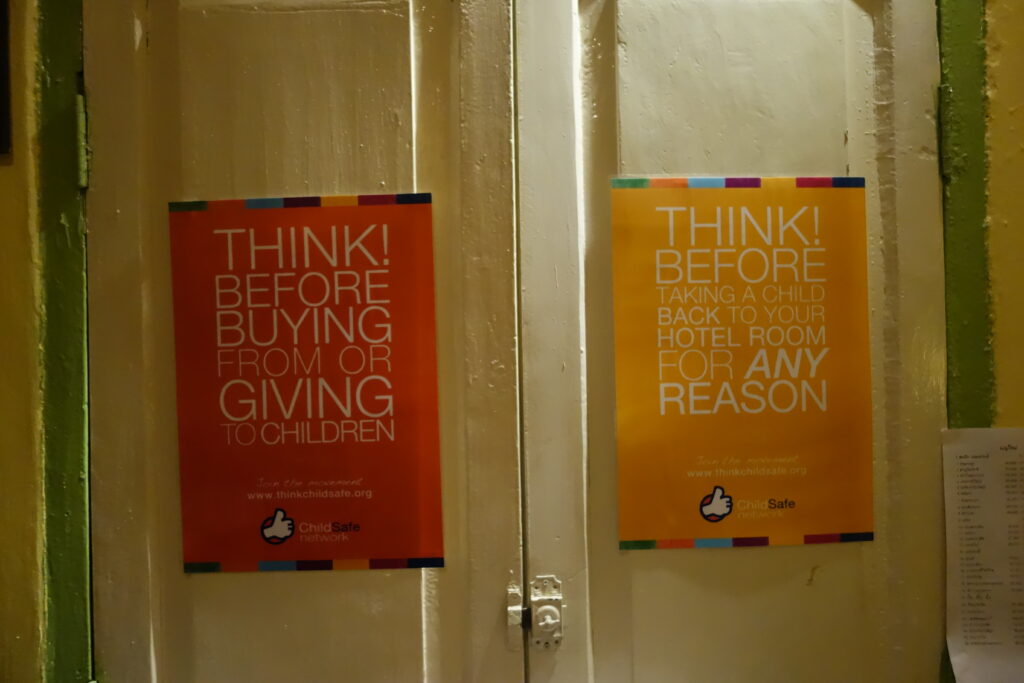

Buying anything from child vendors

This is pretty similar to the one above. It’s easy to think that purchasing a mango from a child is doing good, and you may even pat yourself on the back for spending your money with a local vendor rather than just giving money as charity. Unfortunately this still encourages local families to pull their children out of school sell things to foreigners instead. This may give the family a temporary economic boost, but it hurts the long term prospects of the children.

What can I do instead?

Just don’t buy anything from child vendors. Purchase from stalls with adults instead. If enough people did this that it wasn’t particularly profitable to have their children help them sell things, families wouldn’t have a reason to pull their children out of school.

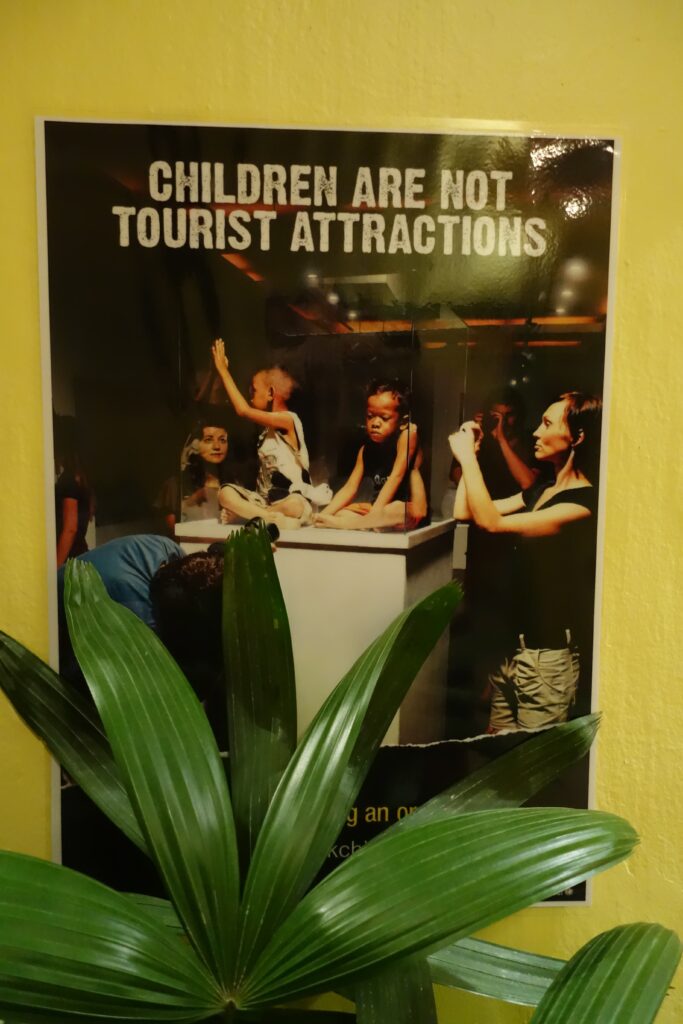

Visiting orphanages

A fairly common activity for travelers to Southeast Asia is to visit an orphanage to play with the children for a day, a week, or a month. A small fee is paid to visit, on the order of 5-10 USD a day. These are children without parents, how could it possibly hurt to visit and spend time with them?

For one thing, because of the fee (sometimes solicited as a “donation”) that is assessed, running an orphanage can be a very profitable endeavor. So profitable in fact, that the capacity of orphanages in Cambodia far exceeds the number of actual orphans in Cambodia. So what is a new orphanage to do, if it has no orphans to shelter? Fortunately, I’m not about to tell you that orphanage owners are out killing parents to create orphans. Instead, they are actually paying small sums to local families to have their children come live at the orphanage. One estimate is that 77 percent of children in Cambodia’s orphanages are not actually orphans. That statistic is sourced from this excellent article from the Guardian on the topic. Studies have shown that long term outcomes are better for children living with family rather than in an institution, regardless of the composition of that family. Think Child Safe (a joint project between Friends-international and UNICEF) is a project dedicated just to combating orphanage tourism.

Now, let’s say that you’ve found an orphanage that you’re sure is full of real orphans. (I’m not sure how you would actually go about this.) You still shouldn’t visit and support the orphanage for two reasons:

- It harms the children. Children need long-term stable loving caregivers to provide for them. The constant stream of people coming for less than a month just causes them endless heartbreak and attachment disorder when they lose those they have bonded with over and over again. It is better for the orphanage to employ qualified local caregivers who will not disappear from the children’s life after a week.

- It can really harm the children. Can you show up, unqualified, to an orphanage in the US and play with the children? Absolutely not. You would have to have qualifications working with children, and you would have to go through a background check to make sure you aren’t a sexual offender. No such rules exist in many of these developing countries which has apparently led to pedophiles traveling abroad to visit orphanages in order to molest the children. The orphanages are largely at fault for allowing this, but can you blame them? By allowing visitors they can make a lot of money. Background checks are expensive; this is one of the reasons why their funding should come from governments and charities, but not from visitors.

A good question to ask yourself before doing anything abroad is, can I do this activity, unqualified, at home? I have a great example of this rule that isn’t suited to appear in this post, but I will write about in the future.

Visiting elephant “sanctuaries”

Go anywhere in Thailand or Laos and you will see ads everywhere to visit an “elephant sanctuary” where you can wash, feed, and sometimes ride the elephants. Most of these are not really sanctuaries in any sense of the word.

Most of the people who see these signs and go to visit love elephants and wouldn’t ever want to harm them. They just don’t realize that the only way to get elephants to allow people to ride them is through a brutal and painful training process that begins when the elephant is young. Here is one blog (out of many) that talks about the issue in detail. We actually talked with some travelers in Chiang Mai who had went to one of these “sanctuaries” and then left immediately when they saw the brutal treatment of the elephants and the bullhooks used to keep them in line. I couldn’t really feel sorry for these travelers who had done no research in advance because even a cursory Google search reveals why you shouldn’t go to places that allow you to ride elephants.

Now, I will admit there are some sanctuaries that bill themselves as ethical and do not allow you to ride the elephants. I’m sure many people think these are acceptable to visit, but I’m personally still not a fan. If their elephants are rescued from the tourism industry (read, riding elephants) I still feel they are supporting that industry by providing those industries a place to dump their elephants when they get too old to be profitable. I would rather see rescued elephants rehabilitated and returned to the wild than be stuck in another tourist attraction – just one where they don’t have to let the humans climb on their backs.

What can I do instead?

One suggestion is to go to one of the national parks in Thailand and try to see elephants in their natural habitat (from a distance of course). We went on a tour in Thailand’s Khao Yai National Park that often encounters elephants. Unfortunately we didn’t wind up seeing any, but we know many other groups doing the same tour on different days did. While it is a bit of a bummer we didn’t wind up seeing any, I’m still happier this way than I would be going to see captive elephants at any sort of “sanctuary”. The cover photo for this post is Khao Yai National Park.

In summary

I’m sure there are many other examples of this problem throughout the world – and it is often difficult or impossible to imagine the negative consequences of what seems like a good action. What all the examples listed here have in common is money. Where there is money to be extracted (especially when it is coming from people with a disproportionate amount compared to locals) there exist perverse incentives to get it.

I am literally sick after reading this blog. Is nothing sacred – kidnapping and maiming children for profit!?!?!? Mankind’s proclivity for evil honestly knows no bounds.

On one hand, thank you for exposing examples of the sinister underside of the foreign tourism industry. But on the other hand, the aphorism, “ignorance is bliss,” comes to mind.

One week from today I will be making my fifth annual trek to the Living Hope orphanage in Mexico that I love and support. What that organization is doing to enrich the lives of disadvantaged kids is the polar opposite of the dispicable “industry” described in your blog. LH is the epitome of unconditional love and sacrifice for the “least of these.”

My fear is that people become so jaded from hearing stories like this that they give up even trying to do good. No! Keep pursuing love, kindness, compassion, generosity, goodness, hope… Don’t let the bastards win.

I wasn’t intending to make anyone jaded – that’s why I put in the “what can I do instead”s. It’s just that we need to be really aware of the consequences of our actions so we can make sure we do as much good as possible.

While I agree with Kim that reading this post was certainly depressing, I’m mostly just impressed that you guys put so much research and thought into your travels. I suppose every post you guys write impresses me with your level of thoughtfulness, but this one particularly.

First of all, my mind is overwhelmed by even imagining the amount of time it must take you to research the basics of all the places you’re visiting. Let alone the time I’m sure it’s taken to research the nitty gritty details of each activity, meal, accommodation, etc, to make sure you’re impacting these places in the most positive of ways. A whole year of consistently doing this is seriously admirable. I imagine it doesn’t seem admirable to you guys, as it’s clearly your MO, but it isn’t for most of the world. Keep rocking with the thoughtfulness, y’all.

LOVE the “what you can do’s”! The first time I experienced an overwhelming amount of negative information (to the point of making me want to give up and do nothing about it) was when I took my first environmental science class at UW’s Nelson Institute. It was a class on the history of the American environmental movement (not very old, btw. started in the 60’s!). Learning about all the ways we’ve damaged ecosystems, species, and even cultural traditions….real, real depressing. But! having the “what you can do’s” makes learning all of that really important and sad information useful. People shut down with too much info, but when armed with positive solutions, amazing change can happen.

I wish I could take as much credit as you give us here, but a lot of these issues were things we learned about as we traveled – we didn’t figure all of this out through research ahead of time.

And I can’t claim we research all the places we eat/stay at ahead of time – we just try to eat and stay at the places that look locally owned. But your comment was incredibly kind – thanks! 🙂

I think I actually took the same class – really depressing. Do you remember the picture of a giant mound of buffalo skulls? (http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-sSxThL7UV_8/U6hvuOqkw2I/AAAAAAAAJfo/ZkXWZdszdZ8/s1600/Bison+skulls+pile+to+be+used+for+fertilizer+,+1870.jpg)

oh man I do remember that photo. agggggggggghhh!!

Ditto Katie’s comment — I’ve learned so much from ALL of your blogs. They are incredibly thoughtful (and well written I may add).

Yes, thank you for the “what you can do”s. If only all tourists took time to learn about these issues or could read your blog. If only all Americans took time to understand the ecological mayhem that led to the birth of the environmental movement (and how the damage continues). If only… etc., etc. etc.

But on a brighter note, having just returned from Yellowstone, I’m glad to report that thousands of bison are alive and well, grazing on the great prairies.